Keep calm and communicate

Real-world examples illustrate the importance of crisis leadership.

PN109 – Crisis Leadership and Communication in Disasters

On October 1, 2017, a gunman opened fire on a country music festival crowd in Las Vegas, Nevada, killing 60 people and wounding hundreds more.

In Las Vegas, the only level 1 trauma center is at University Medical Center of Southern Nevada. But that day, the closest, easily accessible hospital was Sunrise Medical Center, a level 2 trauma center that isn’t usually designated for disasters of that magnitude.

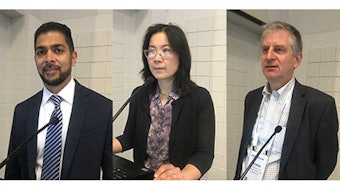

Richard Dutton, MD, MBA, FASA

Richard Dutton, MD, MBA, FASA

“Crisis management has two different components – the big crisis management, and within that the micro event of you being an anesthesiologist who is handed a patient with a gunshot wound and off you go,” he said. “The first step is to call for help. Whether you’re talking about the big crisis or the small crisis.”

Mary Dale Peterson, MD, MSHCA, FACHE, FASA, Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer at Driscoll Children’s Health System in Corpus Christi, Texas, said that ASA’s response in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 was a good example of how to respond to a crisis.

Dr. Peterson said she was able to use her position within the ASA COVID Council that was created that year to help deal with multiple issues that came about as a result of the pandemic – including the ventilator shortage. She said she got a call shortly after one meeting and learned that certain models were predicting a shortage of 200,000 ventilators.

“I said, well, I can’t come up with 200,000, but we have a way to come up with 80,000,” she said. “All that work had been done ahead of time. We had forecast – based on what was happening internationally – what shortages we were going to expect. We were anticipating this. That’s important in a crisis. You have to anticipate the next thing.”

Joseph McIsaac, MBA, MD, MS, FASA

Joseph McIsaac, MBA, MD, MS, FASA

“Understand that typically in a crisis somebody is somehow hurt or injured, people are going to feel threatened, and some folks, depending on the type of crisis, may actually sense that their fundamental beliefs are being challenged. Think back to COVID,” he said. “So, you want to avoid some common mistakes. Things like inadequate accessibility, lack of plain language – using big words or code words or jargon in whatever your specialty happens to be is really the wrong way to do it. You want to use plain language that the average person can understand.”