Are you afraid of code dark?

As cyberattacks increase and intensify, anesthesiologists should be prepared to identify warning signs, pivot processes, and survive the aftermath.

Today, a single medical record has a black market value of at least $250, according to IBM. This steep payout, plus the expanded ease with which hackers can initiate a cyberattack, has led to a rise of security breaches in hospital systems in the United States. In fact, Sagar Mungekar, MD, said: “It’s not a matter of if it will happen, but when it will happen.”

“Code dark” refers to a specific cyberattack that is done on purpose and with malice or malintent, according to Sunday’s panel “Code Dark: Hospital System Cyberattack Preparation and Management.”

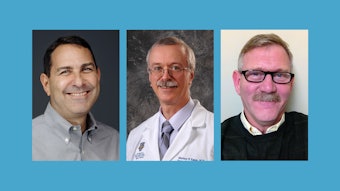

Dr. Mungekar, session moderator and an Assistant Professor, Vice Chair of Data Analytics, and Cardiothoracic Anesthesiologist at Rutgers Health Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in New Jersey, led a succinct review of elements to consider before, during, and after a code dark event. He posed questions to three panelists, who supplied attendees with their firsthand knowledge and experience.

Panelists Olga Leavitt, MD, and Lindsey Rutland, MD, FASA, both work in hospitals that underwent a cyberattack. Dr. Leavitt is a Pediatric Anesthesiologist and Vice Chair of Operations at the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago. Dr. Rutland is a Pediatric Anesthesiologist at Dell Children’s Hospital in Austin, Texas.

Anthony Fritzler, MD, FASA, a Pediatric Anesthesiologist at Akron Children’s Hospital in Ohio, has not personally witnessed a cyberattack, but he is the department lead of his organization’s preparedness plans.

How and why?

A code dark cyberattack can originate in several ways. A hospital employee may click on a web link or email attachment that initiates the hostile takeover. Spear-phishing, or custom phishing, is a sophisticated and realistic technique that hackers use to get people to reveal information.

The warning signs can be subtle, causing people to overlook or misinterpret them. In Dr. Leavitt’s case, she said the hospital had a few glitches in Pyxis that weren’t perceived as threatening. Unfortunately, the next day she came to work to find a widespread shutdown of the network — from the EMR to departmental systems (lab, imaging, pharmacy, blood blank, etc.) and communications (phone, email, pagers). Her hospital couldn’t even track patients as they were admitted to and moved throughout the hospital. In the early hours, she said they only had their personal phones, a few walkie talkies, and overhead speaker announcements to facilitate communication.

In the Ascension cyberattack, Dr. Rutland said the culprit was an off-site server that wasn’t properly secured. The health system uses disparate systems, which turned out to be a benefit in this case as certain departments, including anesthesiology, were able to create an alternate network and get back online more quickly than if all systems had been impacted.

Who and where?

A code dark event impacts everyone, starting at leadership and trickling all the way down to the patients. Step one, Dr. Leavitt said, was to gather the anesthesiology department and evaluate which cases could proceed and which could not — part of her hospital’s standard downtime procedure. From there, department leaders met to look at the following day’s schedule and ensure certain teams wouldn’t be overburdened.

It’s also common for institutions to put together a command center that takes ownership of patient communications and media relations. Panelists agreed it helps to be as transparent with patients as possible to maintain trust in the institution and overall health care industry.

So, what happens after the initial shock and stress of a cyberattack wear off? Where do physicians and employees go from there to come together and move forward?

“After a few days, everybody got in the stride of things, and we settled into a routine. But when the EMR came back up, it was a collective sigh of relief and things got easier,” Dr. Rutland said. “You take for granted how easy it is with the EMR — it adds some things, but it definitely subtracts time and makes things pretty seamless. I’m very grateful for the EMR.”

What’s the answer?

Regardless of fault, code dark isn’t necessarily preventable, but there are some actions an organization can undertake to help hinder hackers. For example, Dr. Rutland said her hospital implemented enhanced security measures like frequent password resets following the event.

Dr. Fritzler said education on what phishing looks like is critical, as is establishing an easy and clear method for employees to report possible phishing.

“Downtimes are usually shorter and last maybe hours, such as scheduled downtimes, whereas code darks and cyberattacks can last weeks or months. Most people are not prepared to deal with that length of downtime and familiarity with downtime,” Dr. Fritzler said. “We don’t get a lot of exposure to going through the steps of navigating through a downtime, especially an extended downtime.”

In addition to regular reviews of if-then scenarios, panelists offered preparatory action items such as

- Advanced training on paper charting

- Established huddle protocols

- Creation of EMR-replicated order sets.

The latter of these can be a vital aid in preserving time, said Drs. Leavitt and Rutland. Clinicians can access packets of common order sets rather than having to individually create these from scratch when pressure is already added.

Another helpful item to consider in advance, Dr. Fritzler said, is a read-only or shadow-only system that runs on a separate network and can be accessed in emergency scenarios. BCA (business continuity access) downtime computers may be beneficial as well, but typically only help for a week.

“I tell people you have to travel back in time, that’s really how you navigate through one of these,” he said, which could mean storing antiquated materials like whiteboards and protocol binders to use in the event of a code dark.